The Arcadian Shepherd

When cruel fate robbed a young footballer of his FA Cup dream, it set in motion an unlikely journey through apartheid South Africa. A tale of football, humanity and faith, this is the untold story of Maurice Hepworth…

“Now faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.”

- Hebrews 11:1

Excited chatter and a silvery glint awakens Maurice Hepworth from his drug-induced doze. His cheery Sunderland teammates surround his hospital bed, holding up the object that has caught Hepworth’s eye and proven a welcome distraction from his crippling stomach pains. Adorned with red and white ribbons and still smelling of champagne, it is the FA Cup trophy.

It’s May 1973, and it’s been a week since Hepworth was admitted to the Sunderland Royal with life-threatening internal injuries that doctors assumed were the result of a car crash. A week in which Don Revie’s ruthless Leeds United have been humbled at Wembley by plucky Wearsiders from the division below. A week in which Sunderland captain Bobby Kerr, goalkeeper Jimmy Montgomery and goalscorer Ian Porterfield have written their names into the most prestigious pages of football’s history books. A week in which the stricken patient they are attempting to cheer up has lost his chance to join them.

The “car crash” in question was in fact the knee of Middlesbrough’s Tony McAndrew, meeting Hepworth’s torso so late and so hard that it ruptured his spleen, burst his small intestine and punctured his bowel.

Although due to be part of the first-team squad travelling to London days later, Hepworth’s role as reserve team captain meant first stepping up for a midweek cup final for the second string, against their bitter north east rivals.

“I was playing centre-midfield that day,” recalls Hepworth, still wincing at the memory, “and I played a 25-yard pass. Then ‘Boro captain Tony McAndrew kneed me in the stomach. He and I had some serious battles during the season.”

“I nearly died on the pitch, as physio Johnny Waters and coach Martin Harvey fought to keep my airways open. They saved my life that night, for sure.”

As he speaks to me during summer’s short window of opportunity between government lockdowns, Hepworth shows no sign of bitterness in missing out on what remains Sunderland’s most recent major silverware. Over the next couple of hours, it becomes clear why. Grateful once again for human interaction as we sip coffee and pore through scrapbooks in his home just seven miles from where Roker Park once stood, Hepworth reveals in unflinching detail a career as fascinating as it is unknown. It is not only a story of football, but of humanity, and of faith.

At just 19 years old, Hepworth’s horror injury was already the second major blow of his fledgling career. Raised in the Northumberland village of Barrasford, as a schoolboy he was originally on the books at Newcastle, relying on his dad to chauffeur a three-hour round-trip through 70 miles of country lanes to get to training.

“Then one day my dad got a letter, unbeknown to me, saying ‘he’s not good enough and we’re not going to sign him’. My dad was more devasted than I was.”

Hepworth still has the letter that had such a profound effect on his father that it later dissuaded him from attending his son’s Sunderland debut as a 17-year-old. It’s a topic that the two of them only revisited many years later.

“It was his biggest regret in life. He said he was scared that I wasn’t good enough and I would be made to look a fool in front of all those thousands of people.”

Standing by his son’s hospital bed in 1973, his dad could have been forgiven for wishing his fears had been borne out, keeping his boy well away from a robust game that was a far cry from today’s cotton-coated variant. And it didn’t take long for the cold-blooded world of professional football to unveil its mental and emotional toil, too.

Sunderland manager Bob Stokoe, now honoured with a statue outside the Stadium of Light, was imbued with cup final spirit when he reassured a bed-bound Hepworth with the promise of a new contract.

“Stokoe came over and whispered in my ear, ‘Don’t worry about anything, I just want you to get better.’ It was a two-year deal. That was class.”

But the sentiment wouldn’t last long. Barely a year later, with Christmas on the horizon, Stokoe had made a stark reassessment.

“I was back as reserve team captain, I felt fit, I was lean and quick, and the cup-winning team were struggling. And we played Notts County, playing most of their first-teamers. We won 3–1 and I’d played well.”

“I was sat in the dressing room and Bob came striding over. I thought he was going to say, ‘top job’. Instead, he knelt down in front of me and said: ‘son, that’s your last game for Sunderland. I’m letting you go, so find yourself another club.’”

Spat out first by Newcastle and now by Sunderland, after being denied a career-defining moment by Middlesbrough, Hepworth’s north-east stomping ground was proving to be one in which he felt constantly stomped on. It took an 8,000-mile journey for him to find salvation. And it would change his life.

In the weeks following his injury, Stokoe had offered Hepworth the opportunity of a loan move to South African side Arcadia Shepherds as a way to build his confidence and regain match fitness. In the 1970s, the country had become something of an unlikely getaway for British players, and even high-profile internationals arrived for lucrative cameos.

But what was intended to be a short stint saw Hepworth and his young wife remain in Pretoria for the season, playing under the welcome guidance of former Rangers full back and Danish international Kai Johansen.

“I had a great time. I got fit, I was playing well, and we won the treble that year. The manager moved me from left back to sweeper, playing alongside a great centre-half, Dave Herholdt. I loved it.”

As cherished as his stint in South Africa was, Hepworth came home energised, now a first-time father with the full intention of reigniting his career at Sunderland. “I even named my son Kai, I never thought I was going to go back there.”

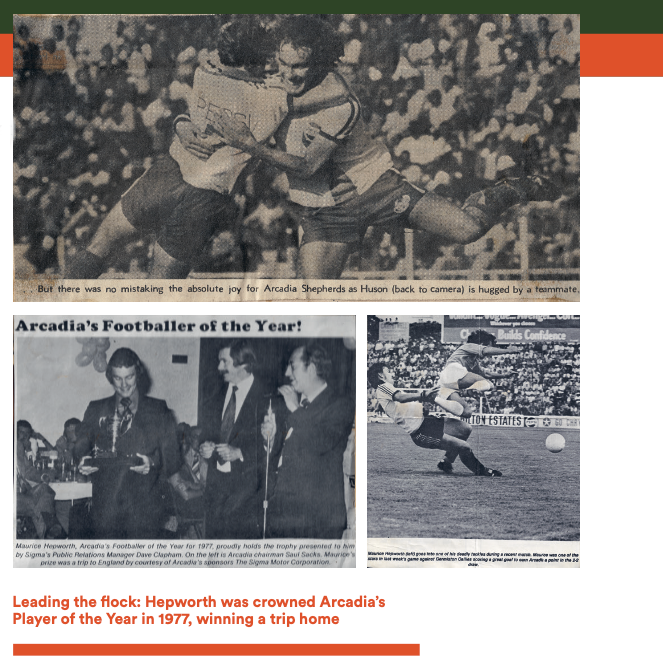

But after being cut loose by Stokoe, and when a loan move to Darlington and interest from Blackpool and Rotherham came to nothing, Africa beckoned once more. Hepworth credits not only the influence of Johansen for his decision to return but also charismatic Shepherds chairman Saul Sacks.

“Saul was such a visionary, one of the most amazing people I’ve had the privilege to meet. He had such an insight in terms of what he felt was right, he had great values and principles.”

And principles were never more important than at this moment in apartheid South Africa, where its football leagues reflected its society; divided down racial lines. This was a pre-Rainbow Nation where the rain was still pouring.

“Eighty per cent of our fans were black. The black fans could come, but they couldn’t play with us.”

Hepworth recalls being invited by one fan to speak at a football talk-in at a hall in the nearby Mamelodi township. About 300 people turned up to hear the Shepherds’ Player of the Year talk about his career before the conversation unexpectedly moved on to politics.

“I can remember it clearly. I said, ‘I came here to play football and I love South Africa, and I love everybody who lives in South Africa. So for me, it’s all about people. It’s not about race. It’s not about colour. It’s about people loving other people.’”

Hepworth grins as he recalls answering a knock at his door the following morning to find two unimpressed police officers demanding to know his whereabouts the previous evening. They proceeded to inform him, in brusque Afrikaans, that he was being arrested for attending a political rally and inciting a riot.

He owes the fact that he avoided jail to the savviness of his chairman. But the episode hinted at the central roles both Sacks and Hepworth would play in one of the most significant moments in South African sport.

Given how sadly prevalent the topic of racial discrimination remains, Hepworth beams with pride as he recounts the events of one historic February night at Arcadia’s Caledonian Stadium in 1977.

“A black player called Vincent Julius had been training with us. We were already pushing the boundaries, we thought there’s no way he’ll ever play for us.”

“But one night we’re preparing to play Rangers, from Johannesburg. The place is packed. And Saul comes in — and he never usually came into the dressing room.”

“He says, ‘At the end of the game we’ll either be heroes, or we’ll all get locked up.’ Then Kai says, ‘Vincent, get changed, you’re playing tonight.’ I’ve got goosebumps now just thinking about it.”

“So we ran out onto the pitch and the crowd went absolutely ballistic. In a great way.”

Julius had been a prolific goalscorer in the Federation Professional League, the only competitive league for ‘coloureds’ (an uncomfortable term still used in the country to refer to multiracial South Africans). His skill and touch made him an instant hit with his Arcadia teammates and, of course, the fans.

“Vincent was such a lovely man,” says Hepworth. “So humble. And he was class. I can’t remember him ever having an off-game.”

If his first appearance raised a few eyebrows, his second would drop jaws. A week later, Arcadia were due to play a crucial game against title rivals Highlands Park in Johannesburg, broadcast on state-run television.

Johansen ensured that Julius’ name didn’t appear in the official match programme, but the striker took his position on the bench. With 20 minutes to go, the manager sent on this bold pioneer and watched with glee as Julius headed the winner with his fourth touch of the ball. Hepworth says the knock-on effect was almost instantaneous.

“It was front-page news, but there was no dissent from any of the football people. There was a bit from the Pretoria hierarchy because obviously, the parliament was in Pretoria. But it definitely helped pave the way, because at the end of that season, they took the top 10 black teams and the top 10 white teams and created a multiracial Premier League.”

“We became the first white team to play in Soweto, with Vincent in the team too. It was an amazing time.”

But there is a dark irony for Hepworth when it comes to telling this uplifting story of humanity and harmony. Because for him, it began a regretful spiral of moral decline.

“For two years after the Vincent incident we were all over the TV, there was a lot of attention. Bobby Moore and Bobby Charlton came over, there were full houses every game. I was 24 then, and I just totally lost the plot. I thought I was Mr Big Deal.”

“I wrecked my marriage and a few lives at that time because I became such a selfish, self-centred, arrogant knob-head. Because you believe your own press.”

Just days after his wife returned to the UK with their young son, Hepworth’s life came crashing down. “My wife flew off on the Wednesday night. On the Saturday we’re playing Berea Park in a bad-tempered local derby.”

“I scored the first goal from a free-kick. Then ten minutes into the second half, I chested the ball down and passed to Vincent. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw their big centre-forward, we’d been kicking lumps out of each other all game. With all my weight on my right leg, he comes over the top. My leg breaks. A compound fracture, my bone popping out through the sock at right angles. It was a mess.”

“I knew straight away that that was it. That finished my career. But that moment, as I hit the ground, my life started again.”

Hepworth describes it as a Road to Damascus moment “with occasional derailments”. But there was no doubt for him that, in front of 23,000 people, it was the day he became a Christian.

“That’s where I met Jesus. But it’s been a long hard road and I couldn’t imagine my life without faith.”

After several lonely weeks of soul-searching, Hepworth had his contract paid up and returned home. No longer the big-name star, attempts to resurrect his marriage and his football career failed. It thrust his faith to the forefront of his life.

In 2010, now happily remarried and thriving in a corporate career, a chance encounter allowed him to return to South Africa during the World Cup, as part of a charity outreach building schools and coaching kids. It was here that he met pastor Angus Buchan, whose words and guidance he credits as inspiring his “foot of the cross” moment. He quit his high-paid sales job and followed his calling.

Today, Hepworth runs a faith-led coaching and leadership programme. School teachers, army veterans and, of course, footballers are among those he offers guidance. In his own words, he is not a “Bible basher”, but rather someone keen to use his vast personal experiences — the setbacks, the mistakes, the achievements — for others to learn from. More recently, battling prostate cancer can be added to the latter.

“I work on reality vs theory,” he explains. “You can try learning all you like out of books. But I want to share stuff with people which is real. There are some serious problems in the world at the minute. I want people to understand that you’re not alone, you can get through it.”

England goalkeeper Jordan Pickford and former Sunderland captain George Honeyman are among the young players who have benefited from time with Hepworth, as demon-burying synchronicity saw him once again working with the north-east clubs previously responsible for his heartache.

There can be no coincidence that the support he is providing is exactly the sort of sage counsel he could have done with in his early twenties. “You use those moments to grow as a person. And that’s had a real effect on who I am now.”

It’s been 47 years since Hepworth lay on that hospital bed, physically and mentally crushed. Back then, he thought that he’d missed his chance to make his mark on the world.

Now, as he thanks me for my visit and says goodbye with a wink and a fist bump, an altogether more serene Maurice Hepworth knows that it was precisely because of his injury, that he’s been able to go on and do just that.

Originally published in issue 9 of NPLH Magazine